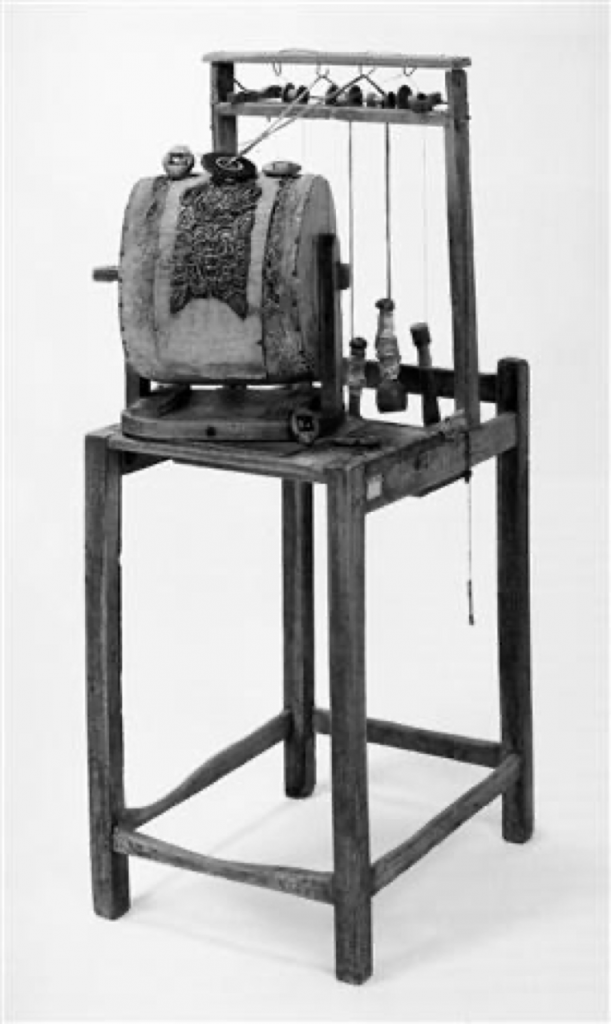

Lily Homer: Spanier Arbeit is a bobbin lace technique. It is the only textile technique that we know of that is exclusive to Ashkenazi Jewish production, and it is made out of fiber that is wound around itself to build up surface area. The wood jig that spanier arbeit is made on looks vaguely similar to the other jigs that bobbin lace is made on, but there are a couple of key differences including the way the bobbins are hung, and the use of gravity through that mechanism to hold the lace in place.

JK: And how did you find spanier arbeit?

LH: I read about it in 2017 in Ita Aber’s book, The Art of Judaic Needlework. I read it right after I completed my college thesis, which was in large part metal-based lace work. The description of spanier arbeit in Aber’s book is amazing. She mentioned that spanier arbeit is considered “unique” to Jewish production. The book included an image of it that I thought was beautiful, so that is when I started trying to Google around and found that there was not much information available about spanier arbeit.

Dr. Ann E. Wild of Freiburg, Germany knows this lace, and she produced some in Germany. She says she is only aware of two other people in the world who still work the technique on the original loom and they are both in Brooklyn — Mr. David Farkas and Rabbi Yosef Greenwald. Ita Aber is an American woman who makes this lace and is largely responsible for the growing body of more accessible essays and literature about it. I’ve tried to reach her but haven’t succeeded yet. And these are the only two women I know of that can make it.

It is not all that rare to see spanier arbeit around in Orthodox communities. I have probably seen it in shul or when I had an Orthodox bat mitzvah, since there were a ton of very fancy articles of clothing around but it obviously did not register. It wasn’t until I read that it was really important in a historical context that I started actually taking interest in spanier arbeit.

JK: So, based on the samples you’ve seen in person and online, could you describe what spanier arbeit looks like?

LH: Spanier arbeit is composed of various patterns: some people call one of the most popular styles of spanier arbeit “fish scales” because the pattern almost looks like semi-circles layered on top of each other in rows, and then subsequently copied up to make rows of layered circles. Spanier arbeit patterns are sometimes more floral. They exist as an embellishment, so the spanier arbeit pattern is usually attached onto the outside of a garment. For example, with skullcaps, they’re made into six triangles of various designs, and then those triangles are sewn together to make a kippah. The fiber used to make spanier arbeit is a pliable fiber, it is bendable, but it is not super bendable, so there is some limit to how you can wrap it around itself. It usually ends up being curved.

One other pattern is called Kasten, where spanier arbeit functions just as a border. Giza Frankel, in her book “Little Known Handicrafts of Polish Jews in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” lists the different kinds of patterns. Atara designs specifically are made of two main parts: the central design “mirror” (spigel) and the border “box” (kasten). A very common design was fish scales (liske). Others are: magen david, menorah, rosettes, stars, hearts (herzele), three snakes (drei schlangen), jug (kriegl), eye (oygele), leaf (bletl), and head (kepl). Different sects of Hasidim embraced certain designs over others, distinguishing one sect’s garb from another’s. For example, the Ruzhin design was a rosette and the Sasów design was heart shaped.

The actual physical form of it is symbolic. In order to make it, lace makers take these long, distinct fibers and wind them around each other. They will take hundreds, if not thousands, of feet of material, and condense it or contract it into a small surface area. The technique is about hiding the amount of material. Essentially, the lace maker tries to package too much of something, something that would not function alone as a decoration, into something that we can recognize as a surface area, by wrapping these materials around themselves.

JK: I’m gathering that there are a few metaphorical interpretations we can make out of that process. Now, do you know of the earliest example of spanier arbeit that exists? Do you know how old it is?

LH: The common belief is that there was a 13-year-old boy named Mordehai Leib Margulies, who fled the khapers (“catchers”) in Ukraine around 1830 and set up a workshop in Sasów, Galicia, which is now Sasiv, Ukraine, and produced what we consider the earliest example of spanier arbeit in Sasów, the one-time center of production. Before the examples from his workshop, I do not know, but it was thought to have been first developed earlier, in the 18th century. Margulies was making the atara, which is the neck band on tallises. I would guess that’s the earliest version. I’ve also seen very early examples of it on tachrichim, in which the neck band is decorated. So this lace does not exist on just the tallises, it exists on funeral smocks, women’s breast plates, waist bands, collars, bonnets, skullcaps, kittels, and cuffs.

JK: So what’s the role of spanier arbeit in attire? What purpose does this lace technique serve on the items you just mentioned?

LH: It is decorative. I think if you’re using it for a religious purpose, one could consider it as having a function, essentially intending spanier arbeit to be a part of any religious service. However, it literally serves a decorative function. It was originally pretty expensive, so it was for special occasions and probably only accessible to the wealthy.

Through all my exploration, I find a tension between this being an exclusive, religious technique, and this being a decorative garment covering. Is it sacred and controlled or is it a lucrative trade subject to changing styles and market demand?

The metals used in spanier arbeit, precious metals, oxidize over time. When they oxidize, they turn green and then they disintegrate. What’s left after the metals disintegrate is the cotton or wool core from the inside, so it looks quite odd. The older samples that have not been saved very well look like decomposing skeletons. They’re essentially half rope and half green metal. You know what the craftsmen intended to do, which is make this perfect adornment, but what’s really there is bubbling to the surface.

JK: What is the history of spanier arbeit production?

LH: The first spanier arbeit factory opened in 1830, and it was popular through the middle of the 19th century. However, by the early 1900s, it had somewhat faded from popular style. But it was still being made by the Shoah. The hub of spaneir arbeit production was in Poland, and 90% of Polish Jews were murdered. Let’s say that there were 200 people making this technique in Poland. That would leave 20 people who might have known how to make it after the war.

And how open are you going to be, after a trauma like that, about making Jewish crafts for Jewish consumption? Probably not very, right? There probably was a period where it wasn’t being made, but I know that it was able to travel outward from Poland, if in very small numbers. There are people who make it in Jerusalem and sell it in the markets there, and there are people who make it and sell it in Brooklyn.

Those are the two places I know it can be bought. But compared to what it was before the Holocaust, it is decimated. And even before the Holocaust, it was much less popular than it was at its peak.

JK: Going back to what you mentioned earlier about Ita Aber saying this craft was “unique” to Jewish production, could you elaborate on what makes this craft uniquely Jewish, and specifically Ashkenazi?

LH: As far as we know, it was invented by Jews in Eastern Galicia or what’s now the eastern part of Poland. It was made exclusively by Jews because they were able to keep it secret enough to maintain the technique. They were able to keep it word of mouth. It was sometimes bought by gentiles, but my understanding at this point is that the vast majority of it was made for other Jews for ceremonial clothing.

[Image description: A black, wooden loom for making spanier arbeit. The rotating drum sits on a raised platform and a frame for hanging bobbins is constructed behind it.]

I think the big wooden loom is a distinguishing feature as well. The process used to produce the lace is a big part of what makes it unique. This is also a reason I’m hesitant to simply look at samples of the lace and make up a way to reproduce it. The jig, with its big rotating drum, and frame for hanging bobbins, seems fundamental to its place in Jewish history.

JK: What differentiates spanier arbeit from other Jewish crafts?

LH: There’s a long history of Jewish metalwork. Jewish crafting on the Iberian Peninsula before the turn of the 11th century is a good example of a flourishing metalwork culture. I think other groups would commission Jewish handiwork, which helped this culture develop.

When I think of other Jewish crafts, I think of paper cutting, ceramics, and manuscript illumination –– very different types of media from metalwork. Like with similar techniques to spanier arbeit found in other cultures, there is a lot of overlap with these crafts as well. When small populations interact and share traditions, and since Jews migrated (forcibly) for thousands of years, there is bound to be stylistic similarities, if not duplications.

There’s also one style of architecture that is exclusively Jewish, which is the wooden synagogue. There were a couple hundred in Poland and they were all burned down in the 1940s. There are approximately 12 left, and they are all in Lithuania. The insides of these wooden synagogues are intricately painted. They’re full of color, aphid and floral and geometric designs on the inside, whereas the outside is a nondescript wooden building.The torah cover is very intricately designed and the door to the Torah arc is supposed to resemble the door to heaven.

I think spanier arbeit and all of these other examples fall into a category of intricacy. There’s a common thread of intricacy and detail in Jewish art, which speaks to the importance of craftsmanship: our labor over these objects can represent our commitment to G-d. Synagogues and metalwork are also materially opposed to paper cutting projects, which are gorgeous, but ephemeral. There is no expectation of longevity or permanence.

https://www.needlenthread.com/2020/09/a-practical-guide-to-needle-lace.html

https://www.oidfa.com/organisation/young-lacemaker-grants-scheme/

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/57009/57009-h/57009-h.htm